Beneath Warsaw, the Dead

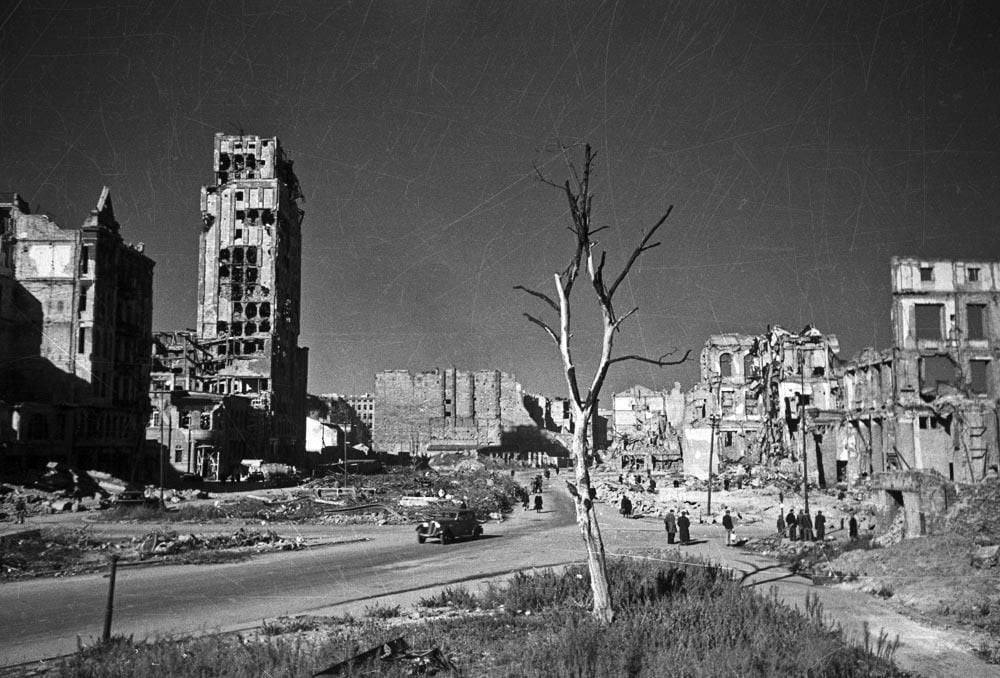

When the Red Army entered Warsaw in January 1945, it did not discover a defeated city, but an absence. Warsaw was no longer a capital, not even an ordinary ruin: it was a field of stones, pulverized bricks, gaping cellars, a carefully manufactured urban desert. Where more than a million inhabitants had lived, almost no one remained. And beneath the rubble, the dead.

After the failure of the Warsaw Uprising in the autumn of 1944, the German authorities decided to wipe the city off the map. This was not blind destruction born of combat, but a methodical demolition. District by district, building by building, Warsaw was dynamited, burned, emptied. Survivors were expelled, the wounded often finished off, hospitals burned with their patients inside. The city was meant to die even without witnesses.

When the inhabitants slowly returned in the spring of 1945, they walked on land that had become a cemetery without crosses. Very quickly, clearing operations revealed what everyone suspected: bodies everywhere. In the cellars where families had taken refuge. In collapsed stairwells. Beneath the rubble of hospitals, schools, churches. In the streets themselves, sometimes simply covered with dust and bricks.

Improvised mass graves were countless. In Wola, in Ochota, in the Old Town, thousands of civilians had been summarily executed in just a few days, often by machine gun, sometimes burned alive. During the clearing work, hastily dug communal pits were unearthed, but also isolated, forgotten bodies, sealed into stone by the collapse of buildings. Some were nothing more than bones mixed with mortar. Others were recognizable only by a button, a shoe, a wedding ring.

But not all would ever be found.

Many bodies were destroyed by fire. The Germans had systematically set the ruins ablaze, sometimes after locking civilians inside. Other victims were crushed under tons of debris, rendered inaccessible by unstable structures. To clear every cellar, every basement, would have meant indefinitely delaying reconstruction, at the risk of deadly collapses. The city had to live again, even if that meant building over the dead.

Today it is estimated that 200,000 to 250,000 civilians perished in Warsaw in 1944. Only a portion of their bodies could be exhumed, identified, and reburied with dignity. The others remained where the war had left them: beneath sidewalks, rebuilt buildings, squares brought back to life. Warsaw rose above them, layer by layer, as if the city itself had become a mausoleum.

This is why Warsaw's memory is so particular. Its monuments do not always mark a precise place: they designate an absence, an invisible multitude. Each district has its symbol, its stele, its wall engraved with names. But many names are missing. Many of the dead have no grave. Their burial place is the entire city.

The reconstruction of Warsaw was an act of defiance as much as of mourning. One could not wait for all the dead to be found; it would have taken decades, perhaps a century. So the city was rebuilt. Repopulated. Children played above sealed cellars. Trams ran along streets beneath which bodies still lay. Life resumed, not through forgetting, but through necessity.

Even today, during construction work, human remains are sometimes discovered. The past then rises to the surface, briefly, before being buried once more, this time with rites, names, recognition. Warsaw has never ceased to be a city inhabited by its dead.

It does not hide them.

It lives with them.

SWSP

(Translated from French)